News Staff

News Staff![]() -

June 27, 2023 -

Environment -

groundwater

earth's axis tilt

-

3.8K views -

0 Comments -

0 Likes -

0 Reviews

-

June 27, 2023 -

Environment -

groundwater

earth's axis tilt

-

3.8K views -

0 Comments -

0 Likes -

0 Reviews

DLNews Environment:

It was only in 2016 that scientists realized water significantly impacts how the Earth rotates. A study has found that our thirst for groundwater has measurably tilted the planet's axis.

Researchers at Seoul National University modeled the movement of the Earth's axis, first using only glaciers and ice sheets, then adding different groundwater extraction scenarios. The results closely matched observations.

Unquenchable Thirst for Groundwater

For cities, towns, and villages in drought-prone regions of the world, groundwater extraction is a lifeline. But aquifers are not inexhaustible, and excessive pumping lowers the water table and makes it harder to replenish the resource. During wet years, rain and gushing streams often sink into aquifers and help them recover, but the process takes time.

A cubic meter of water is profoundly heavy, and the extra weight adds up. A new study demonstrates that the amount of water we pump from underground is significant enough to shift Earth's axis, and that shift is occurring much more rapidly than expected.

The findings are based on gravity surveys of the depletion of underground reservoirs caused by irrigation in Western North America and northwestern India, as well as a measurement of the shifting weight these changes cause. The study found that between 1993 and 2010, the displacement of groundwater caused a shift in Earth's rotation axis of about 4.36 centimeters per year.

Earth's Axis Shifts

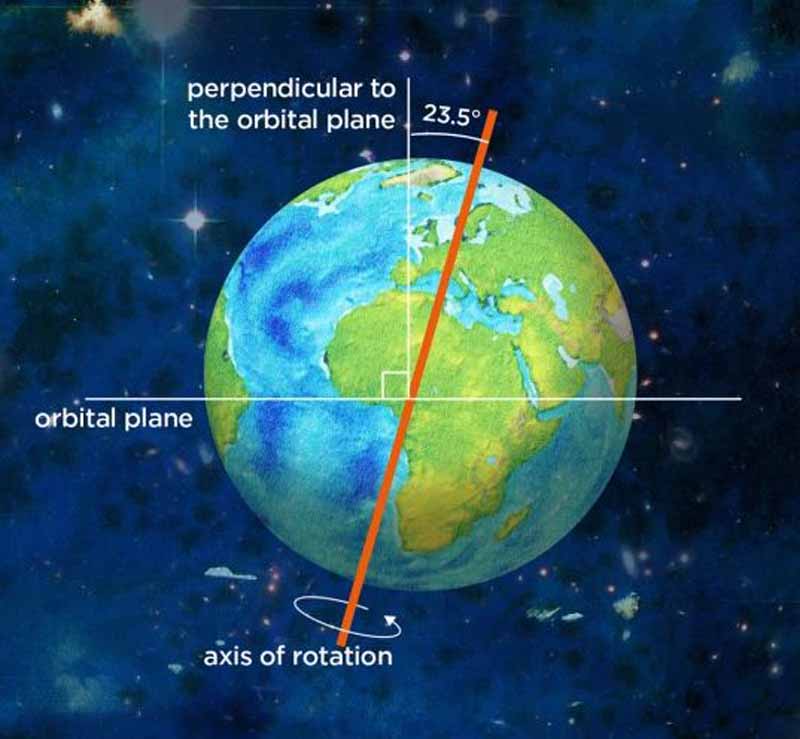

While spinning on its axis like an off-kilter top, Earth wobbles in response to changes in its mass distribution. That can be caused by melting ice caps, glaciers, ocean currents, and hurricanes. But groundwater extraction has also made a big difference.

In a new study published this week in Geophysical Research Letters, researchers found that we have shifted the axis on which our planet rotates by pumping so much water. That shift is equivalent to the weight of about two airplanes, or 1.7 inches per year.

The scientists first modeled the movement of the axis based only on ice loss, but this didn’t match up with reality. So they added the effect of pumped groundwater, and their model closely matches the observed data. They estimate that between 1993 and 2010, humans pumped 2,150 gigatons of groundwater, most of which flowed into the oceans. Most of this occurred in western North America and northwestern India.

It's Not Just Melting Glaciers.

Most people envision rivers, wetlands, and lakes when they think of water. But 30 times more freshwater is stored underground and out of sight in groundwater.

Rain and melting snow percolate into the ground, saturating the spaces between soil particles and cracks (fractures) in rock. This saturated zone is called an aquifer.

Groundwater can then seep through the ground or flow from an aquifer into a wetland, stream, lake, or river to become surface water. Groundwater also supplies drinking water for many people and helps with crop irrigation when rain is scarce.

However, groundwater pumping can have negative impacts. When the aquifer level drops, it can impact the surrounding ecosystem. For example, riparian vegetation that lines rivers and wetlands may die due to low water levels. Land subsidence can also change how the aquifer interacts with surface water bodies, resulting in contaminated or salty water. These changes can be irreversible, Seo says.

It's a Big Deal

Over the decade between 1993 and 2010, human pumping and drainage have removed 2,150 gigatons of water from natural reservoirs and shifted it to the oceans. That water weight is large enough to change the axis on which our planet rotates or cause its rotational pole to move in polar motion.

While greenhouse gas emissions and melting ice contribute to polar motion, scientists didn't expect that pumping groundwater would also play a role. But that's what they found when they plugged in data on how much groundwater was extracted and where it went.

The resulting model showed that the polar motion was influenced by a shifting of mass weight to the oceans, particularly in mid-latitudes. This is important because the locations of these changes matter for how much they alter polar drift. While the shifts caused by this water redistribution may not immediately impact everyday life, they do have long-term implications.

Humans Pump So Much Groundwater That Earth's ...

By News Staff![]() 0

0

0

930

4

0

0

0

930

4

4 photos

Desert Local News is an invitation-only, members-based publication built on fact-checked, non-biased journalism.

All articles are publicly visible and free to read, but participation is reserved for members—comments and discussion require an invitation to join.

We cover local, state, and world news with clarity and context, free from political agendas, outrage, or misinformation.